Strange Attractor

Art Basel, Switzerland

Booth M11

June 13 - 19, 2021

In the mathematical field of dynamical systems, an attractor is a set of states toward which a system tends to evolve. An attractor is deemed strange when its dynamics are chaotic and difficult to predict. Ouyang’s work in Strange Attractor responds to a quote from abolitionist clergyman Theodore Parker, later cited by Martin Luther King, Jr: that “the arc of the moral universe is long but it bends toward justice.” The quote has been deployed alternately as a mantra of hope and license for complacency. With attention to what historical formation has actually “bent” toward, the works in Strange Attractor are invested in how endeavor coexists with unresolvable complication.

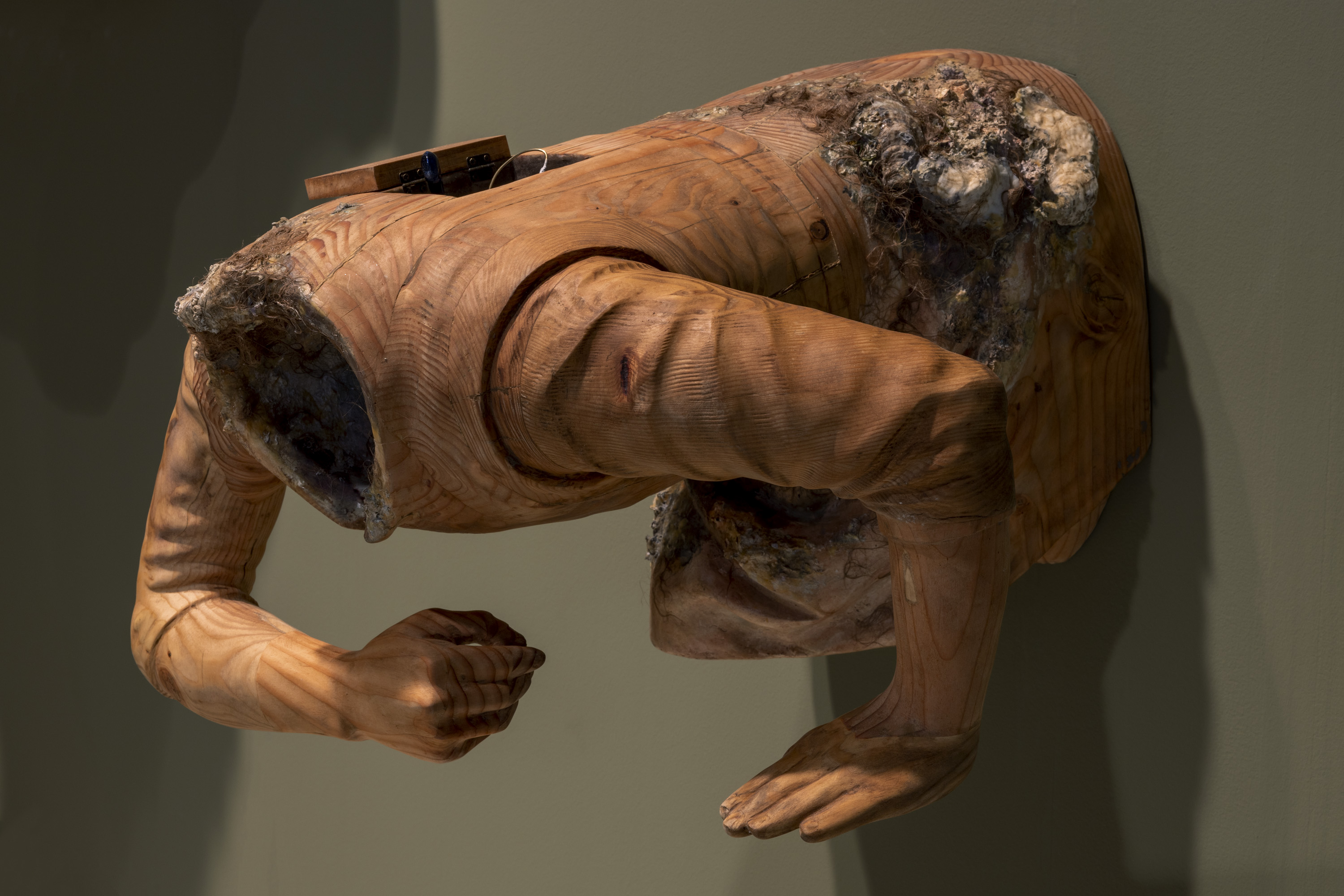

The figurative postures of Ouyang’s reliquaries are drawn from four Balthus paintings of Thérèse Blanchard, the 11-year-old working-class girl who served from 1936-39 as Balthus’ muse. The reliquaries, as supposed containers of fetish objects, address the parameters of desire, longing, and cruelty. Following long-standing controversy surrounding Balthus’ use of young girls as models, the work hovers in the shadow of historical fact, neither exonerating nor condemning.

Two new fonts, referencing holy water vessels in churches, incorporate carved stone, wood, altered found objects, and customary raw eggs. Both fonts also include vessels filled with bleach, soaking manuscripts of Ezra Pound’s Cathay and Ovid’s account of the myth of Caenis and Poseidon. The fonts are presented on a central pedestal modeled after the bed from Balthus’ 1938 painting The Victim, which features an undressed young girl who appears dead—assumed by some to be modeled after Blanchard. The bed frame, skeletal and torched, is presented absent of the girl, with a faint imprint of her vacated body visible in the bedclothes.

A free-standing sculpture presents a replica of Edmonia Lewis’ bust of Union officer Robert Gould Shaw, carved by hand into an antique wooden statue of Guan Yin—gender-fluid deity of mercy—dating from roughly the same time as Lewis’ piece. Lewis was arguably the first BIPOC American sculptor to achieve international recognition within a western artistic tradition. Coming into prominence during the Civil War, Lewis was at once supported and exploited by abolitionists. Tiring of tokenization, she financed a relocation to Rome by selling plaster replicas of Shaw’s bust shortly after his death in battle. This act of capitalizing on both Shaw’s body and “heroic” death stands as a counterpart to Balthus’ exploitation of young Thérèse: two vastly different ways of metabolizing the “muse.”

Prior to leaving the US, Lewis avoided representation of Black or indigenous feminine subjects, knowing that such works would be dismissed as self-portraiture. This principle coincides with Ouyang’s queer ethics of refusal, in terms of representation and (il)legibility. In taking up a representation of Shaw via the spectral proxy of Lewis alongside the abstracted presence of Thérèse Blanchard, Ouyang relates historical valences of power and self-definition to victimhood, psychological transference, and the simultaneous humiliation and impossibility of representation.

The titular film Strange Attractor is projected from beneath the bed frame. The film is structured around one night that Ouyang and their much older white benefactor spend driving around the neighborhood surrounding the Smithsonian American Art Museum, where Edmonia Lewis’ magnum opus The Death of Cleopatra is on view. As they orbit this sculpture in a mile-wide radius, Ouyang and their benefactor—a professor of astrophysics—converse about chaos. At some point, the artist sleeps. At sunrise, Ouyang awakes and recounts their dream to the camera, in a slippery restitution of agency stripped from the original dreaming Thérèse.